For centuries, painted textiles from India reached the far corners of the world through extensive networks of trade and commerce. These fabrics not only narrated folktales and mythological epics on their surfaces but also wove within them the diverse socio-economic history and regional artistic knowledge of the peoples of the subcontinent. Textiles decorated with the hand-painted technique of Kalamkari and the tie-dyeing process of Bandhani are prime examples of how traditional artistic practices continue to carve out a place for themselves in contemporary markets.

The design company 11.11/eleven eleven has dedicated itself to promoting regional art forms and intangible living heritage since its inception. In these images, we see how they have created a unique kind of textile that represents the varied landscape of India, made real through its diverse craft practices. This material is made by blending two distinct traditional techniques: Kalamkari and Bandhani.

Kalamkari – which consists of the words kalam (pen) and kari (craftsmanship) – was initiated centuries ago by folk singers and painters. The art form eventually evolved into something truly remarkable, as the spoken word was brought to life by painting stories on fabric. Today Kalamkari continues to flourish in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, where it is practised by master craftsmen, with knowledge of it handed down from one generation to the next. Creating Kalamkari textiles requires extensive technical skill and precision that can only be accomplished by seasoned artisans who have honed their abilities over many years.

Bandhani is derived from a Sanskrit word for “to tie”. It is one of the oldest tie-dye techniques and has been practised in South Asia for more than four thousand years. A dye-resist method, it involves pulling the fabric into tight, small knots, which are tied firmly with strings and then dyed to create remarkably delicate and intricate patterns. The practice of Bandhani still thrives in the states of Gujarat and Rajasthan. Its splendid patterns are mostly seen on veils (also known as odhanis), turbans and saris. And today is also used creatively for modern and cutting-edge fashion.

The product seen here is first adorned with the Kalamkari technique in a floral design. Kalamkari pieces, traditionally done on cotton or silk, involve 17 individual steps, each one as meticulous as the next. It begins with the treatment of the chosen fabric. The cloth is first treated in a solution of cow dung and bleach and is left to soak for hours. After this step, the fabric is dipped into a solution prepared with buffalo milk and myrobalan powder. Myrobalan is a dye and a mordant extracted from the ground nuts of the Terminalia Chebula tree, which grows abundantly in India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand and South China. Myrobalan is popularly used in India and Southeast Asia for cotton fabrics, as it creates a light, warm colour on the cloth and also provides a good base for over-dyeing.

Once the cloth has undergone these treatments it is washed again and dried in the sun. After the fabric dries and becomes stiff, it is flattened and stretched over a flat surface. Kalamkari artist Thilak Reddy, seen here, begins to sketch the motif on the surface of the cloth using a charcoal and turmeric stick. Reddy has been practising this art form for several years and has adapted the traditional technique in modern ways to create wall hangings and wearable everyday garments.

Kalamkari artists conventionally use colours made up of natural dyes. These are extracted from sources like crushed stones and mineral salts, powdered flower petals, leaves, roots and seeds. Artists primarily draw on earthy tones such as mustard, rust, green, black and indigo. The black colour is made by blending jaggery with water and iron filings. Mustard or yellow is obtained by boiling pomegranate peels or by mixing and boiling myrobalan powder with water and setting it aside for hours. Shades of red are extracted from the bark of the madder plant. Blue is obtained from the indigo plant, and green is created by mixing yellow and blue colours together. After the colours are prepared, the artist begins to paint the designs directly on the cloth.

After Reddy finishes the outline for the pattern, he begins to use an ink pen known as a kalam. Those with a thin tip are used to draw outlines for the designs, and kalams with broad tips are used to fill in the colours. This implement is made of a bamboo reed with a cloth wound around it, which also has a substantial amount of wool tied around. The bamboo has a pointed tip that is dipped into the dye, thereby allowing the spongy, woollen ball around the pen to soak up the dye. When the craftsman begins to work with the kalam and fill in the colours, he lightly presses on the woollen ball. In the images shown here, you can see how the artist carefully paints the floral motifs in red, green and yellow.

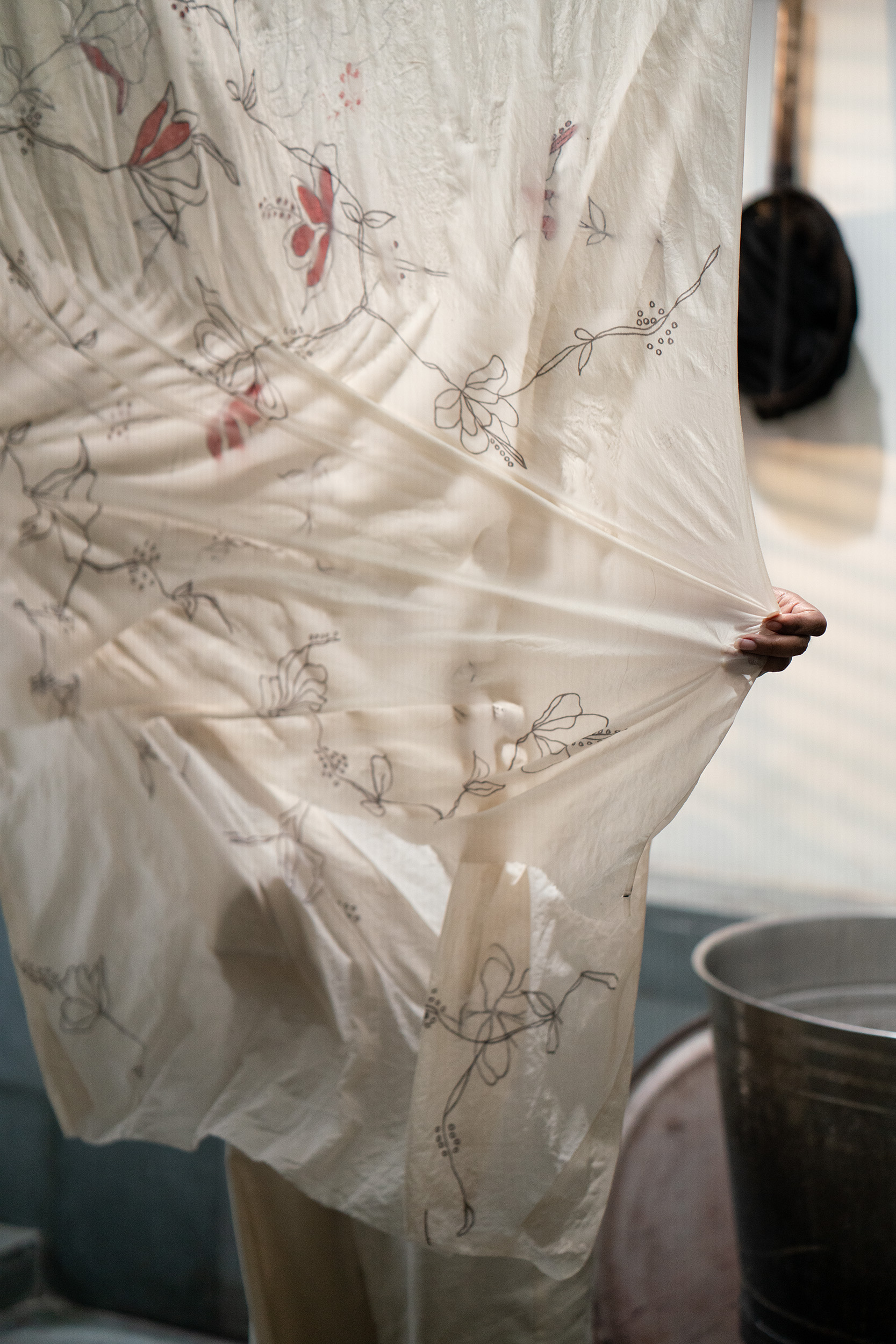

Once it has been painted, the fabric is then boiled in water and left to dry. After the cloth is completely dried, the pattern is further enhanced with the indigo colour by 11:11’s Adheep, shown in these images. Once the stages of the laborious Kalamkari process are completed, the next phase of the larger design begins: the Bandhani (tie-dyeing) method. For this, the Kalamkari fabric is sent to the studio and workshop of Abduljabbar M. Khatri in the Kutch district of Gujarat.

Bandhani:

Jabbar, as he is known to many, grew up watching his mother and aunts tying Bandhani, then watching neighbours dye the cloth. Jabbar teamed up with his brother Abdullah to reinvigorate this tradition by creating unique and innovative new designs. Together they have refined this age-old practice over the years.

In the images from Jabbar’s workshop, we can see that the process for creating Bandhani patterns begins with tracing the design on grease-proof paper and puncturing it with holes using a stylus along the outline. The cloth chosen for the tying is first washed thoroughly to soften it and remove any impurities, as clean fibres are better at absorbing the colours. Once the cloth is dried, the stencil is then placed onto it and dusted with a blue powder (or neel, as it is locally called) created from a solution of indigo mixed with kerosene. As the powder seeps through the paper’s perforations, it settles on to the fabric beneath, creating the blueprint of the design that the Bandhani artists will follow.

The fabric with the Bandhani pattern is firmly attached to the top surface of the painted Kalamkari panel. The Bandhani makers then meticulously begin tying individual knots on the cloth, also known as bundi or bindi, with strings. The art of tying Bandhani is conventionally practised by women, while the dyeing is performed by men. The women use a sharp, metallic ring-like tool on their fingers known as a nakhaliya. It resembles an extended metal nail and is used to pluck the fabric. A glass tube known as a bhungari enables the artisans to tie the thread easily. This is a time-consuming exercise where the artists, as seen in these images, deftly bind the small knots on the cloth according to the traced design – thus creating the signature circular pattern associated with Bandhani. The more intricate the motif, the more spectacular the impact it has on the textile.

Now that the two techniques of Kalamkari and Bandhani have been harmoniously combined to create this exclusive design, the fabric is then dyed in indigo by Jabbar. This stage is by far the most technical and arduous step in the entire process. In Kutch, the vocation of dyeing is practised by a Muslim community known as Khatris. For them, dyeing is not just a profession but a way of life. The community has exclusively practised and developed complex dyeing techniques over several generations.

The dyeing process of this exquisitely designed cloth starts by dipping it into indigo vats. This rich and deep blue hue is obtained by dissolving indigo cakes into hot water that has been mixed with different chemicals in the right proportions. The quality of the indigo bars is first tested by immersing them in water; only those bars that float to the surface are used, while those that sink to the bottom are deemed unusable, due to the impurities they contain. The preparation of indigo dyes requires calculated precision; several environmental factors also need to be considered. These include sunlight and the Ph levels of the water used. Indigo dyeing is essentially a chemical transformation wherein the right levels of oxidization determine the precise shade that will emerge. The fabric shown in these images is dipped in multiple vats, as no vessel can be used more than once in a single day. In some of the pictures we can see how the indigo-dyed cloth develops a dark green colour when it is first removed from the containers and then slowly turns blue with oxidization.

Once the craftsman has fully immersed the cloth in the dye, he uses great strength to squeeze out the excess colour, then puts the cloth in plain water and boils it. In order to further enhance the fabric’s colour, the cloth is dyed once again, this time in red dye derived from plants of the Rubia genus (typically the madder plant). The powdered form of the colour is mixed in a pot of boiling water. The artisan gently dips the cloth in the vessel, and with gloved hands and a wooden stick, submerges the fabric repeatedly.

After the colour of the textile has been created through this complex dyeing and over-dyeing process, it is now ready to be washed again and left to dry. Once the cloth is completely dried under a hot Indian sun, the numerous Bandhani knots are carefully opened. The cloth is stretched out some more once all the tying threads have been removed. What remains is a myriad of colours and patterns. The resulting textile is a true testament to the ingenuity, adaptability and technical expertise of Indian designers and craftspeople.