Pleats are multiple folds introduced to a garment to make it visually distinct by adding volume and movement. The earliest examples of pleating can be found on linen robes traced back to ancient Egypt. The traditional art of pleating involves gathering and securing numerous folds on a piece of fabric by pressure, temperature and steam. The term Plissée itself originates from the French word pli, for pleat, derived from plier, to fold. Plissée originally referred to a fabric that was woven or gathered into pleats. It is also widely known as crinkle crêpe.

From the mid-sixteenth century until the middle of the seventeenth, prominent figures such as Mary Stewart and members of the renowned Medici family helped establish the popularity of the elaborate pleated neck ruff, which formed part of an ornate clothing ensemble. This extravagant style marked the upper echelons of European society, although pleated collars also started appearing in traditional costumes by the eighteenth century. At the end of the nineteenth century, individually folded cardboard moulds came into use for pleating. With the onset of the industrial revolution, the first pleating machines were introduced to the market, making pleated fabrics and garments widely available and more affordable. Since 1990, computer-controlled pleating machines have been used to fabricate pleats of different sizes. Today, the preferred fabric for pleating is lightweight with a crinkled, puckered surface that can be shaped into ridges or stripes. The traditional practice of adding continuous folds to clothing remains a part of our everyday wardrobe.

In Germany only a few studios remain committed to the traditional craft of pleating. One of them is the Gießmannpleating workshop in Berlin’s Charlottenburg district. Producing both hand- and machine-made pleats, the family firm is managed by Sigrid Gießmann and her daughter Stefanie John. Their clients include several haute couture and fashion companies as well as over three hundred opera houses, theatres, and film studios from all over Europe. To feature the pleating technique, made/in collaborated with the Gießmann atelier to create two striking garments working with traditional craft practices. This partnership resulted in a pleated version of the made/in signature shirt with detachable front panels and a top constructed by using handmade sunray pleats in a unique way.

Today, the material best suited to making perfectly symmetrical pleats is pure polyester. This is because the creases remain intact even after washing, for a permanent effect. Haute couture brands often experiment and use mixed fabrics in their pleated garments. The most common pleating styles are accordion pleats, side pleats, and box pleats. Accordion pleats resemble an accordion and are symmetrical, with each side of the pleat being the same length. In a side pleat, one side of the accordion pleat is shorter than the other, so that the pleat folds to the side and creates a flat, even surface. A box pleat is obtained by taking two side pleats, turning one of them over, and bringing both together on the fold. Combining different kinds of pleats will yield a variety of interesting results and textures.

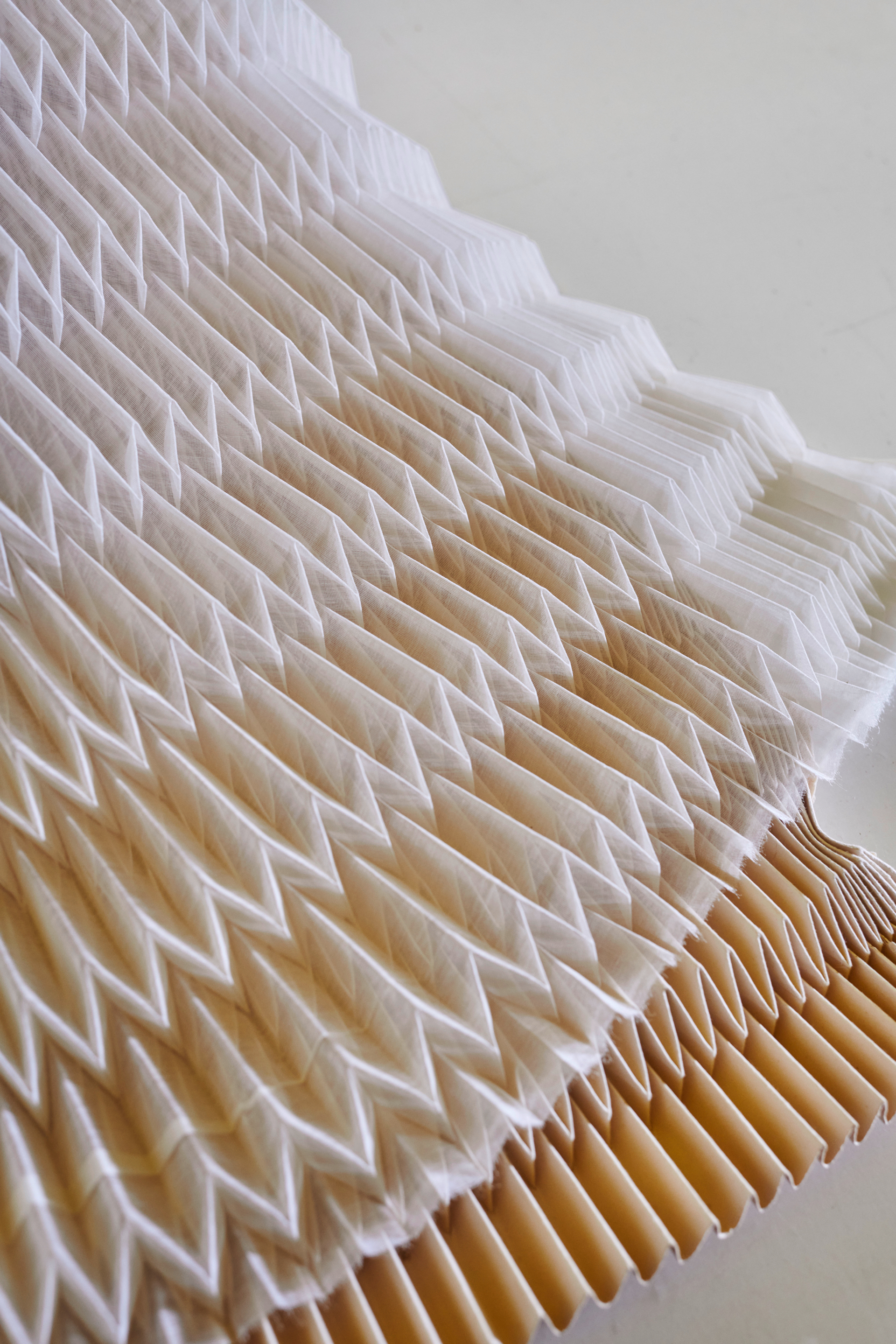

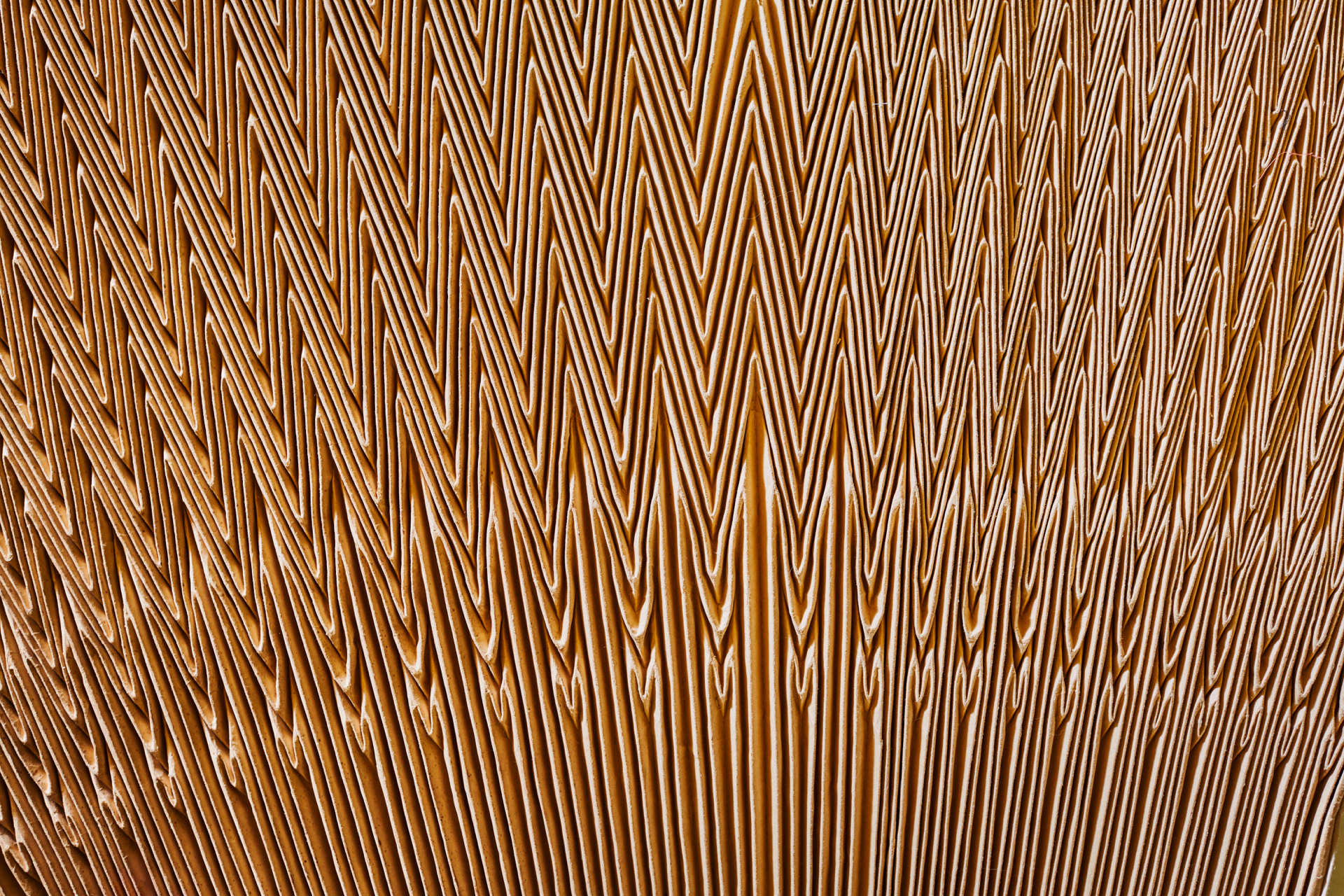

This wealth of different pleated patterns begins with handmade paper moulds made of a tear-resistant special paper impervious to steam and heat. The fabrics are folded in the paper moulds, and take on the patterns through the application of steam. The construction of a pleating mould is sandwich-like, with the fabric pressed in between. The most popular style is the sunray pleat, primarily used for pleating skirts. It resembles a half-circle with conical pleats that are narrow at the top and become wider at the bottom. The size of the pleat at the bottom of the skirt depends on the radius of the garment: the smaller the radius, the larger the pleats; conversely, the greater the outline at the top, the smaller the pleats.

Before the pleating process begins, the selected fabric must be prepared by cutting it in a semicircle and smoothing out all the creases with an iron. The cloth is once again flattened by hand to ensure an ideal texture for pleating. In the case of very thin and delicate fabrics such as chiffon, there must be no draught while smoothing the cloth into the mould. To ensure that the fabric placed inside the mould is completely even, the craftsperson can also gently blow on it to prevent wrinkles from appearing on the surface. Once the cloth is evenly placed inside, it is then gradually closed inside the mould and steamed in the oven.

The symmetry of pleats made by hand comes from years of knowledge about the fabric, the mould, precision and technical training. A primary difference between hand pleating and machine pleating is not only in the manufacturing process but also their final appearance. For instance, sunray pleats are folded by hand using a pleat mould and then heated in an oven with steam, whereas machine pleats are made with tiny folds that are four millimetres wide and can be set into the fabric. The firing temperature and the number of pleats set, per minute, can be adjusted individually.

Continuing with the example of a sunray mould, its semicircular pleated moulds are fanned out on a large table, after which the top and bottom parts are separated. The bottom form is stretched onto the table and weighed down using metal weights while the top portion of the mould is kept aside. Once the mould is prepared, the fabric is placed and is then meticulously made smooth inside the mould by hand so that it fits perfectly into its grooves. Once the cloth is firmly secured inside the bottom part of the mould, the folded top section is placed on the fabric and is fixed in place with weights. The mould is then folded from the outside to the middle until it lies congruent with the bottom form. This ensures the folds are steamed accurately in the oven.

The pleats are generally steamed in a specialized kiln. The moulds are heated inside an industrial steam oven, without the aid of any chemicals, for sixty to ninety minutes at a temperature of 180 degrees Celsius. The duration of the steaming process is determined by the volume of the moulds inside the oven. After this is completed, the moulds are removed from the kiln and set to cool overnight. Once the mould has cooled down completely, it is carefully opened and fanned out; the upper and lower portions are separated gently to remove the pleated fabric pressed in between. If the pleating has been executed with technical precision, the individual folds will stay in the fabric for many years to come.