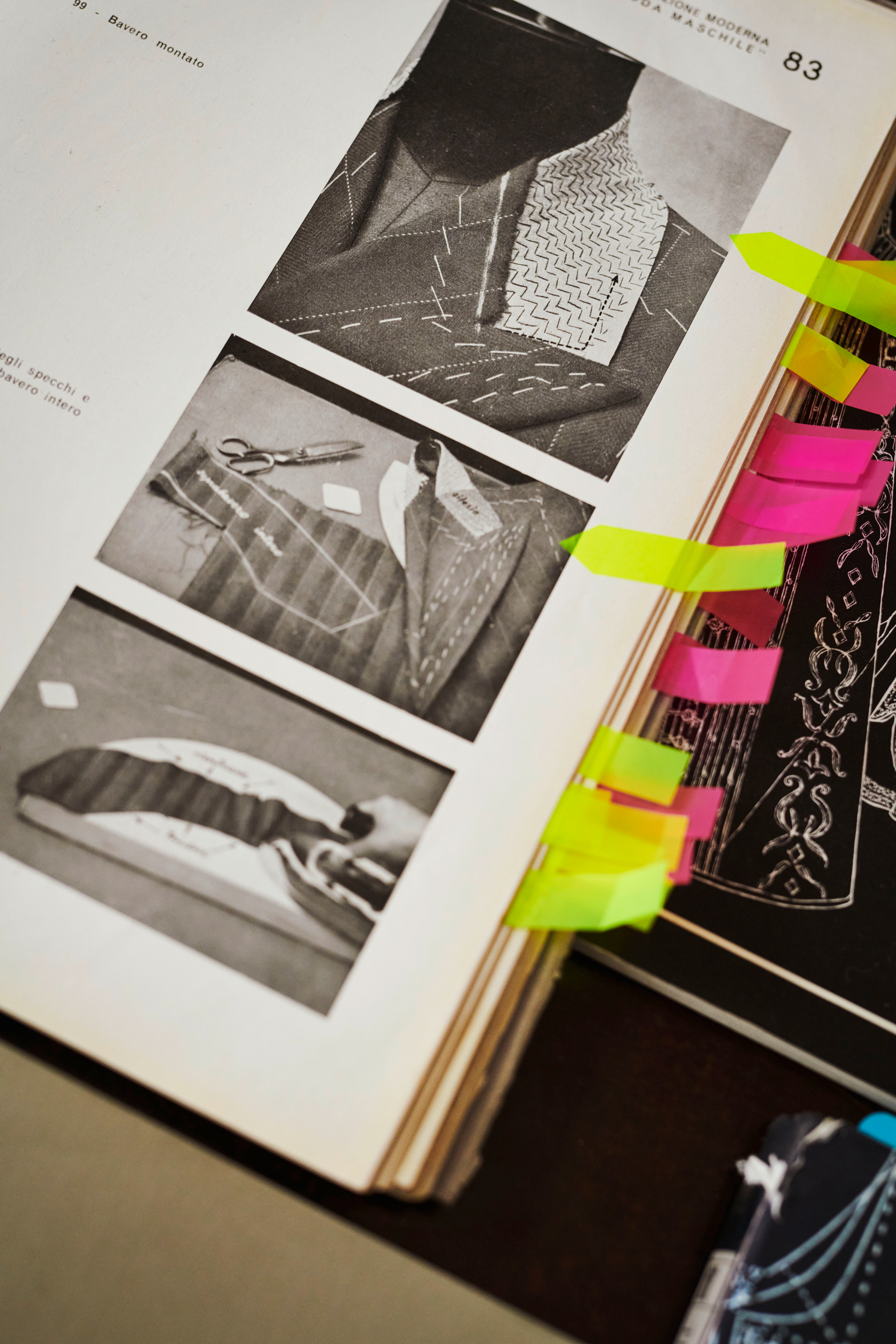

Pattern making is an art form that is often overlooked in today’s fast-paced, consumer-driven, ready-to-wear fashion landscape. It is the pattern makers who give concrete form to a designer’s inspiration by creating the perfect cut. The craft of pattern making has evolved over several centuries, particularly in the field of menswear. The profession of bespoke men’s tailoring has existed in Germany for over a millennium and encompasses the region’s rich cultural history. At the end of the nineteenth century, Michael Müller invented the original Müller & Sohn cutting system in Munich, allowing for designs to be converted into cuts with a precise fit. This cutting system still leads the world market in design today and has been constantly used and adapted in innovative ways to meet the demands of modern consumers.

For this collaboration, made/in worked with designer and pattern maker Kai Lehmann, who demonstrates the process of creating a custom-made men’s jacket. Lehmann is currently a professor of model design, pattern design and CAD (Computer Aided Design) at the University of the Arts Bremen. He was previously a guest lecturer in the menswear master’s programme at the Royal College of Art in London. His experience includes working for prestigious brands such as Vivienne Westwood and Hugo Boss as well as running his own menswear label called Suit E. Here Lehmann takes us through the details for creating a perfectly tailored suit.

The transition from pattern making and bespoke tailoring is fluid. Tailoring as a craft requires a combination of skill, precision and attention to detail. A customized tailor-made suit can cost anywhere from three- to six thousand euros – and upwards. It could take from four to six weeks to create, including at least three fitting sessions. The price of a well-made suit depends on the expertise of the tailor, the equipment used, and most importantly, the quality of the fabric.

In the spring of 2022, UNESCO will decide whether the craft of tailoring – and terms such as “tailoring” and “men’s tailor” – will be included on the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Germany. Technical terms such as “bespoke work” and “men’s tailor” also need to be protected. Similar terms such as “bespoke” or “made-to-measure” are only suggestive of customized tailoring, but that is only partly true. The aim is to preserve this craft along with the methods and services associated with it.

Tailoring any garment first begins with design inspiration, which is given a definitive shape through a pattern. This craft is a collaborative exercise between the designer, the pattern maker and the seamstress. While the garment is being made, there is a constant exchange of ideas among these practitioners, and changes are incorporated accordingly during this creative process.

The basic construction for the sample used here comes from the classic example of a jacket from the nineteenth century, which consists of the front, back, and side panels with few visible seams. The first component to consider is the shape of a customer’s body and the trend the consumer would like to emulate. A finely tailored jacket must feel like a second skin on a person’s body, for which precise measurements are vital. Every handmade jacket is meant to cater to the client’s own proportions – specifically the waist, shoulder, type of shoulder pads, and the width and length of the sleeves. The rule of thumb for tailor-made jackets is that they must fit the customer’s body as if his figure were symmetrical.

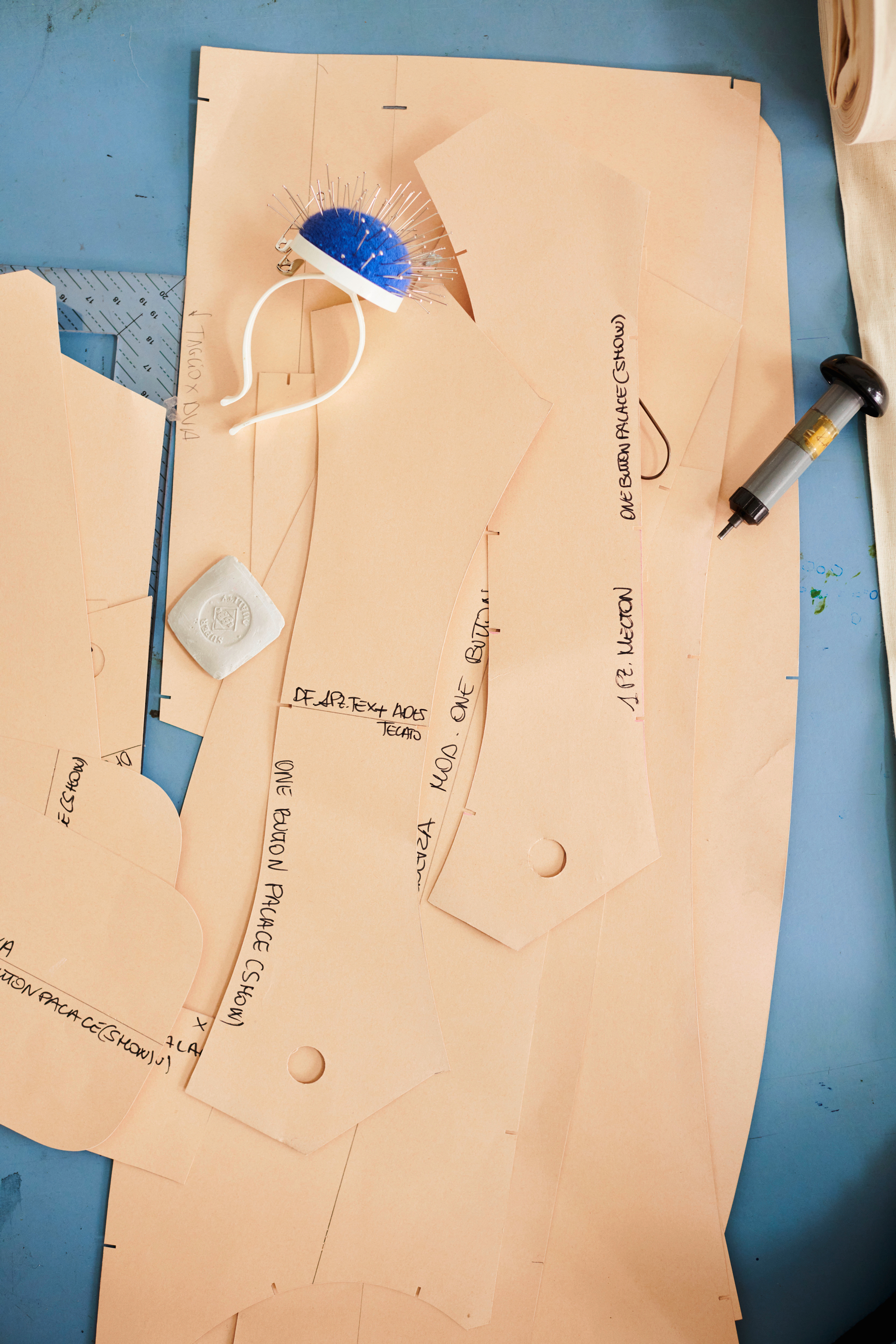

However, the fit of any garment is primarily dependent on the client’s personal choice. In bespoke tailoring, every customer has his own personal pattern made, which consists of individual parts; shapes such those of the lapel, pockets, lower edge section, and the curve of the jacket are all separate components that make the pattern for a whole garment. A combination of these distinct elements is how the outline of the pattern is then transferred to the calico or the original fabric.

It is important to have notches, or marks on the cutting line, that identify where two pieces match so that one knows how the individual pieces should be sewn together. The number of clips on the sleevehead are indicators of the division of the width when stitching. This may vary depending on the type of the chosen material, be it wool, silk or thin cotton.

The cutting provides all the information that a sewing workshop, pattern studio, or ready-to-wear department requires. In a ready-to-wear workshop, the basic cut and pattern made for the first fitting are fabricated with calico, a material similar to linen but stronger, with a seam allowance of one centimetre. Cotton is also favoured, as it distinctly shows the shape of a cut and is neutral. In bespoke tailoring, the basic pattern cut is made by the master craftsman in the original fabric, which is hand-stitched with a generous seam margin of three to four centimetres and is altered according to the customer’s figure and preference. The transformation of the two-dimensional cut into a three-dimensional form and shape of a jacket is an art form in itself.

The indicators of a well-tailored jacket are the perfect shape of the chest and the sleeve interfacings. To achieve the perfect form for the chest, the interfacings are made from horsehair or synthetic material, which ensures stretchability and ample movement around the chest area. The jacket breast is piqued, which means it is underlaid with special woollen linen or tailor’s linen and stitched into shape by hand.

An important part of the cutting process is that no fabric should be wasted, this applies not only to customized tailoring with expensive fabrics but also to ready-to-wear production. Therefore, if possible, two or more pattern pieces are placed inside each other for cutting, however, the fabric grain needs to be observed.

After the sewing is completed, the pattern maker must check the precision of the stitching by placing the garment on a mannequin. The craftsman must observe the fitting of the harness jacket on a mannequin; the pattern maker checks if it is straight and if the wearer would be able to move in it comfortably.

Shoulder pads are placed beneath the jacket to provide support in the area between the shoulder and the sleeve. The width of the shoulder depends on the fashion preferences trending at the time. A feature that reflects high standards is how the sleeve is inserted; it should fit well and be comfortable and flexible. The insertion points for the sleeve are marked so that the pivot area in the armpit region does not change. The challenge here is in the containment width in the sleeve and how to distribute it so that no seam or dart is needed in the sleevehead.

The drape of the sleeve is important while constructing a tailor-made garment. Earlier, sleeves were more curved, but today they have two seams and only a slight curve towards the front. It is also important for the jacket to fall elegantly when it is placed on a hanger. If the armhole fits, then the pattern made from calico can be used for the sleeve.

Once the shape has been determined after the first fitting, the production and then the finishing steps of the process begin. The sleeves require specialized seamstresses; so-called fish are made of fleece and sewn into the inside of the sleevehead. This is meant to control the fullness and fall of the sleevehead, which allows the seamstresses to elaborate on the shoulder. Additionally, the collar is made from felt, which gives a good fit and a soft texture when placed around the neck.

The next step is to prepare the jacket for fitting. The key here is to insert the chest interfacings as described above. When all the basting threads are removed after the fitting, they will no longer be visible. Hence the fabric retains its natural texture and doesn’t appear too stiff. The customer only feels it when wearing the garment. These days, prefabricated interfacings are also used, which simulate a similar comfortable feeling while wearing the garment. After everything is marked, the fitting for a made-to-measure jacket can begin.

In bespoke tailoring, the two front pieces are piqued, and the breast interfacings are tacked in place before the fitting. At the time of the fit, if something is not in line with precise measurements in the original fabric, the tailor can make adjustments to the jacket via the shoulder seam and the back side seam. In anticipation of possible alterations to the jacket based on the customer’s figure – and to avoid excessive cutting away of the original fabric – a seam is pre-stitched with a margin of two to four centimetres. Due to this generous seam allowance in the custom-made suit, the sleeve can still be corrected on the customer’s body. The collar is also pinned while the jacket is on the client. And if the neck opening also needs to be checked beforehand, it must be pinned first.

Buttonholes handsewn by a tailor are an important component of a customized suit. They are stitched during production after the last fitting as soon as the precise sleeve length has been determined.