Please tell us about the beginnings of your label and your work as a designer.

I was a part of a World Bank Project, aimed at generating design led livelihoods for about 4 years. I wanted to continue working with crafts, especially Sujani after it came to a halt. I had switched from being a part of a funded project to establishing a self-sustaining business with design lead livelihoods as the central objective. As a designer I had to think product, processes for creating directly with craftsmen in a conscious and feasible way and making it work as a business. The products were created over interactive creative workshops with artisans. The product, processes, and the consequent model of operating were seen on the cusp of design, craft and art. It has its own challenges. I focused on 'one of a kind pieces' for the first couple of years. Later added more ready to wear to the collections.

You have been working with hand embroidery and lately other craft techniques for quite a few years. What brought you to these crafts and what motivated you as a textile and fashion designer to use these techniques in your work?

I wanted to find and give my design practice a purpose. Although I wasn't sure what that could be. While exploring I found it in crafts. Working closely with artisans I discovered how crafts are closely intertwined with social, cultural, political, economic, spiritual and many other aspects of an artisans life. Through my work with crafts and craftsmen, I started creating products that helped me discover a vocabulary that I could call my own.

What kind of embroidery techniques are you using? Can you explain the origins of the Sujani technique from Bihar and how you started using it?

Traditionally, Sujani is a special quilt made in Bihar by recycling a number of worn out sarees and dhotis in a simple running stitch that gives it a structure while ornamenting it. The technique of sewing together pieces of old cloth, layered together, has its age old function in two belief systems- Ritual function- it invoked the presence of a deity, Chitiriya Ma. The lady of tatters. In it is enshrined the holistic Indian concept that all parts belong to the whole and must return to it. The other purpose of stitching of old pieces of cloth together was to wrap the newborn; to allow it to be enveloped in a soft embrace, resembling that of its mother. When dissected, the term Sujani reflects the above mentioned functional nature of this practice- su means easy and facilitating, while jani means birth. They have also been ritualistic creations becoming primary component of the Kobarghar (nuptial chamber)and gifts to family members. Sujani was the first craft cluster assigned to me at the Asian Heritage foundation. I wasn't keen on working with embroideries at the time.

How does the collaborative process between you as the designer and the artisans who do the embroidery take place? Can you please describe the process from the origin of an idea to the execution of the embroidery and the making of the garment? What role does mutual creative exchange have to play in it?

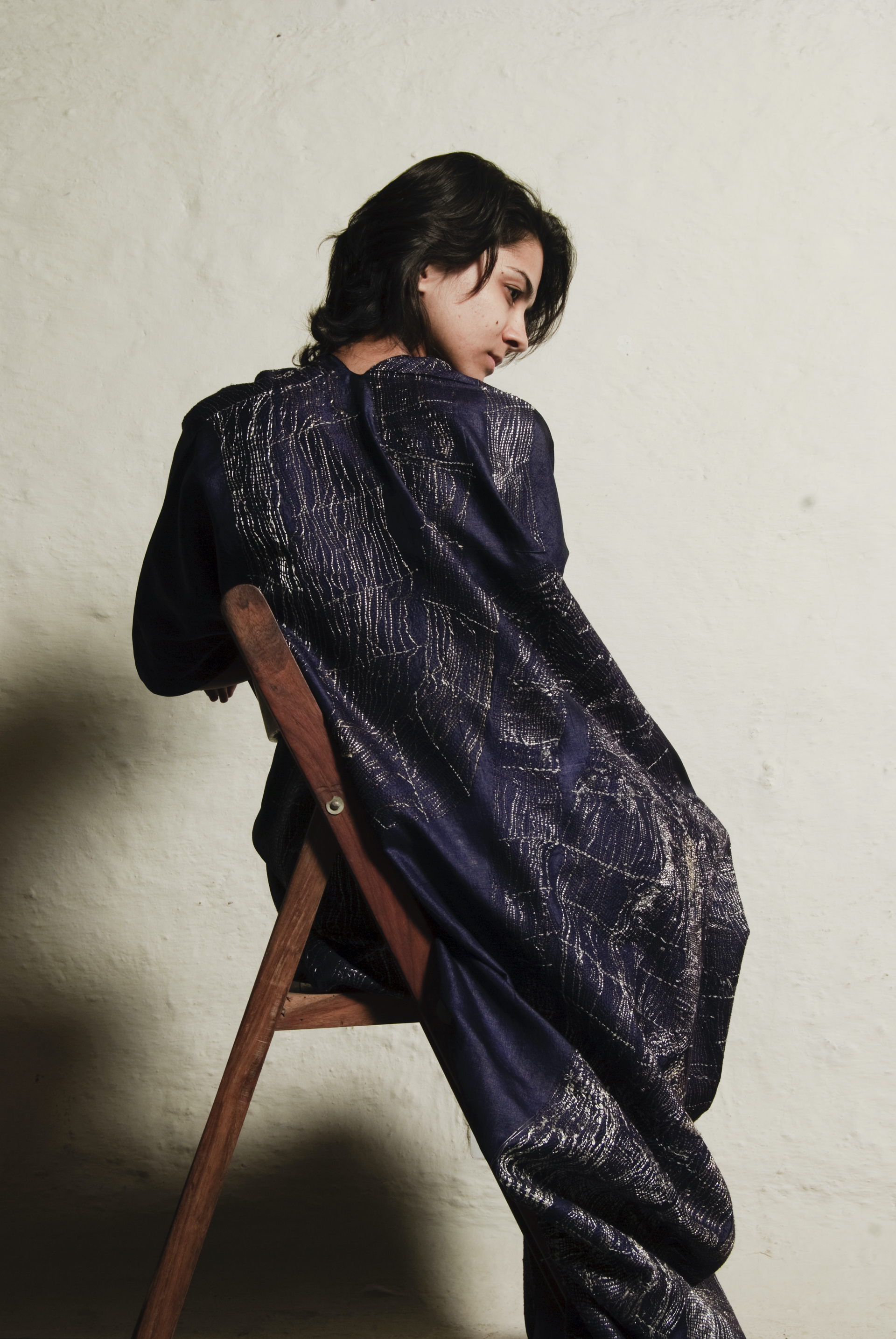

The study of the craft, of its literature and practice helped set the tone of my explorations. The surface created in sujani out of simple running stitches, moving in transient intensities, asymmetries, sizes and colours suggest natural processes and also reflect the spirit of the creator. The conspicuous character enticed me to explore textured surfaces using this traditional craft. I generally reach them with initial ideas. First is translating ideas into stitch with artisans. The translation needs to be aesthetically convincing, effective application of the techniques used in Sujani. The applied stitch also needs to be strong to keep fabrics together, to be able to survive time. We play around with it to create larger areas of embroidery that are non-repetitive.

I engage with artisans in interactive creative processes to enhance the artist in them. Over intriguing give and take and inconceivable twists and turns, emerges a unique design vocabulary that connotes timelessness, highlighting the quirks and anomalies that arise out of the process of creating. Ideation/direction for the range, sourcing and preparing fabrics for embroidery, styles for the garments, stitching, finishing and all the rest are taken care of at the studio in Delhi.

Is innovation what will make crafts relevant in the future? What is the significance and importance of tradition for the essence of a craft?

Continuum is key. Roots are very important, so is growing, furthering, reinventing. Like the spiral of life. Both tradition and innovation have their own space. They enable each other. Innovation can keep the crafts engaging and relevant with the times.

What kind of business relation do you have with the artisans you work with? Are they full time employed or are they working independently?

They work with us on a workshop basis. Artisans have shared with us that our workshops/ training helps them fetch more work from other vendors, government schemes and other programs. Workshop trainings act as a certification.

Where do you see the future of handcraft? Is a meaningful future only possible in the sector of luxury?

There has never been any one solution for addressing concerns, in fields as vast as crafts. Luxury helps nurture craftsmanship, skills and crafts. It encourages imagination, creativity, dreaming. It costs thus only a few people can afford it. A relatively economical line can provide more consistent work to craftsmen, as it is more affordable hence faster selling. Empowering craftsmen as independent thinkers can open them up to their true potential. I am sure there can be many in-betweens, a spectrum of ideas and engagements that can each build a more affable ecosystem for crafts. So, each of us should do what we can, within our own capacities, in our own ways as individuals, companies or organizations.

How does the collaborative process between you as the designer and the artisans who do the embroidery take place? Can you please describe the process from the origin of an idea to the execution of the embroidery and the making of the garment? What role does mutual creative exchange have to play in it?

The study of the craft, of its literature and practice helped set the tone of my explorations. The surface created in sujani out of simple running stitches, moving in transient intensities, asymmetries, sizes and colours suggest natural processes and also reflect the spirit of the creator. The conspicuous character enticed me to explore textured surfaces using this traditional craft. I generally reach them with initial ideas. First is translating ideas into stitch with artisans. The translation needs to be aesthetically convincing, effective application of the techniques used in Sujani. The applied stitch also needs to be strong to keep fabrics together, to be able to survive time. We play around with it to create larger areas of embroidery that are non-repetitive. I engage with artisans in interactive creative processes to enhance the artist in them. Over intriguing give and take and inconceivable twists and turns, emerges a unique design vocabulary that connotes timelessness, highlighting the quirks and anomalies that arise out of the process of creating. Ideation/direction for the range, sourcing and preparing fabrics for embroidery, styles for the garments, stitching, finishing and all the rest are taken care of at the studio in Delhi.

What is the role of innovation in craft from your point of view? How does it interplay with the significance of the tradition and essence of a craft?

Continuum is key. Roots are very important, so is growing, furthering, reinventing. Like the spiral of life. Both tradition and innovation have their own space. They enable each other. Innovation can keep the crafts engaging and relevant with the times.

What kind of business relation do you have with the artisans you work with? Are they full time employed or are they working independently?

They work with us on a workshop basis. Artisans have shared with us that our workshops/ training helps them fetch more work from other vendors, government schemes and other programs. Workshop trainings act as a certification.

Where do you see the future of handcraft? Is a meaningful future only possible in the sector of luxury?

There has never been any one solution for addressing concerns, in fields as vast as crafts. Luxury helps nurture craftsmanship, skills and crafts. It encourages imagination, creativity, dreaming. It costs thus only a few people can afford it. A relatively economical line can provide more consistent work to craftsmen, as it is more affordable hence faster selling. Empowering craftsmen as independent thinkers can open them up to their true potential. I am sure there can be many in-betweens, a spectrum of ideas and engagements that can each build a more affable ecosystem for crafts. So, each of us should do what we can, within our own capacities, in our own ways as individuals, companies or organizations.

Swati Kalsi is a textile and clothing designer well known for bringing contemporary relevance to the time honored handcrafted textiles of artisans. She’s been working with handcrafted textiles for over 10 years and works closely with artisans.

All Photos: @Courtesy of Swati Kalsi