The politics of credit in the Indian fashion industry

I.

Firoz Alam, the head masterji[1] at Lovebirds, a popular contemporary Indian clothing brand, has an active instagram account. On one of his posts, an image of a Lovebirds dress, he wrote the caption: “it is my work”. In the Indian fashion context, the translation of the word work, “kaam”, has multiple meanings that are visible and tactile, material and conceptual. But Firoz masterji’s use of the English word ‘work’ for this caption would most commonly be read as ownership over the labour that went into producing this garment – both manual and creative.

When the Lovebirds founders shared this anecdote to a close friend group, all of whom are in the Indian creative industry, there was laughter, but it wasn't entirely comfortable. Though one friend piped up to say how cool it was that their masterji was on instagram (a response that sounded dated as soon as she said it), the general feeling was that he had perhaps crossed a line. However, in doing so, his act also raised important questions about credit, and the validity of established work hierarchies in the age of instagram.

I wondered:

If this was his work, what was the designer’s work? Is the ownership over creative labour – which was historically within the exclusive remit of the relatively upper caste and class designer – now publicly shared between designer and employee? What does this do to the politics of credit?

I decided to explore this anecdote further, as the echoes of our group’s response stayed with me for days. In follow up conversations, I learned that what was happening at Lovebirds was happening in many design studios. But, in most cases, designers do not, or maybe cannot do anything to confront the issue, even if they experience it as violating. Reasons range from the fluid, “democratic” nature of instagram to perhaps a greater fear – losing their most valuable resources.

II.

There are two public secrets in the Indian fashion industry: 1) the quality of Masterjis, and karigars (embroiderers) determine the success of the business and 2) the family business model, ubiquitous in the industry, promises longevity.

During my fieldwork, which I conducted for my PhD research in anthropology (2011-2014), I became well aware of these secrets, and interested in how they operated to sustain established hierarchies in the industry. In almost every interview I conducted with a designer, regardless of his or her seniority, ample verbal credit was endowed upon his or her craftsmen. “They are the heroes of my studio,” was a phrase that verged on cliché; other polite redundancies included calling them “the true talents” of the business. The more sentimental designers commonly referred to their head masterji’s as fictive kin – “like brothers” or “just like family”. This phrase that is often invoked by upper middle and upper class families in India to articulate alliances with their domestic staff.

Through the years after my fieldwork, ways of crediting non-designers in the business – the craftsmen and tailors – thankfully evolved beyond from verbal credit. Public articulations of care can be quite touching: I recall that at almost every pero fashion show I attended, the designer Aneeth Arora invited all her craftsmen, tailors, and embroiderers to fill the last two rows of the hall. Only later, when her show passes became coveted beyond supply, the team would stand at the back, but nonetheless be in full attendance, dressed in the brand.

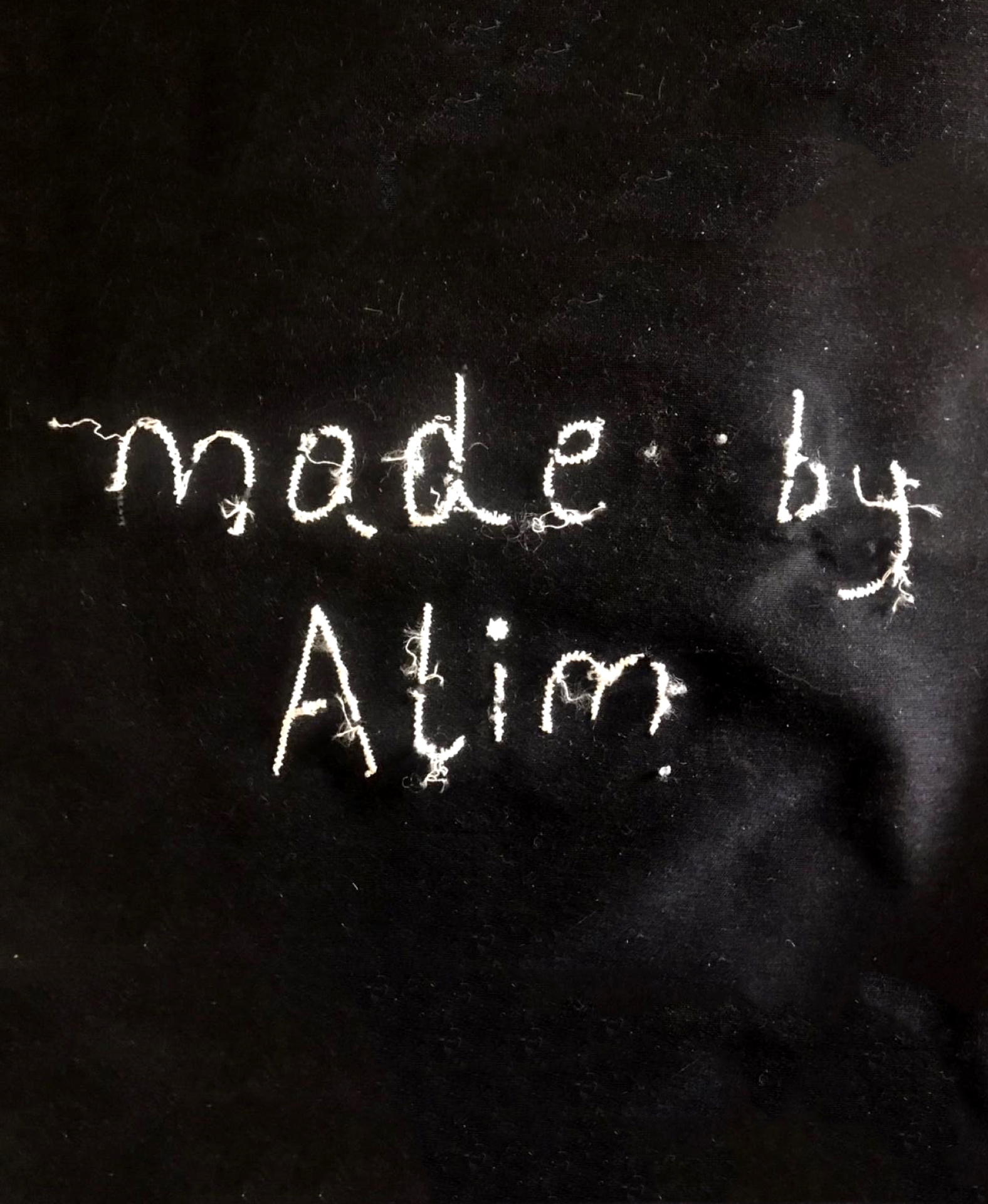

As “I made your shirt” campaigns took over the West (most often communicated via images of garment makers holding up hand written signs), Indian designers followed. This movement for recognition was heightened after the tragic 2012 Rana Plaza fashion factory fire, which brought up urgent questions around the lives of people who make fast fashion. Designers also began exploring new strategies of credit: this worked to acknowledge the talent that goes into their production, and also position themselves as ethical. Thanks to this shift, consumers now designers selling garments with their craftsmen’s initials, or first names embroidered on them. Meanwhile, instagram accounts of fashion brands were saturated with posts that detailed the ‘the making of xyz piece,’ often accompanied by the hundreds of labour hours that went into production, tallied in the caption.

However, while many of these attempts to credit craftsmen and tailors fairly may be genuine and are certainly a marked improvement from the treatment of Indian craftsmen in the colonial period, our ideas of what constitutes credit – an integral part of what we go on to define as “ethical fashion” -- remain top down. As upper caste and class designers or owners of the means of production, even in our attempts to be ethical, we implant foreign, assumedly universal ideas of credit on to those less powerful than us. This often ends up, unintentionally, reproducing the inequalities of labour that we claim to reject.

The simplest way to address this problem, if we care to, is perhaps the most radical. We could ask what the non-designers who work to produce Indian fashion want. We could ask them what they would like to be called, instead of “like family.” We could ask what they consider credit, if not their initials embedded on to a garment that costs many times their salary. We can even dare to ask if creative credit even matters to them, if it is not immediately monetizable?

[1] Masterji is the Hindi word for a senior professional, who has an expertise in dressmaking.