The beginnings of design in India are often attributed to the establishment of the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad in the state of Gujarat, in 1961. It was based on “The India Report” of 1958, a set of recommendations made by designers Charles and Ray Eames after a three-month trip across the country, for “a programme of training in design that would serve as an aid to the small industries; and that would resist the present rapid deterioration in design and quality of consumer good”.[1] NID was founded with a grant from the Ford Foundation and supported by the efforts of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Pupul Jaykar – a prominent advisor on culture to the Indian government – and the industrialists Gira and Gautam Sarabhai.

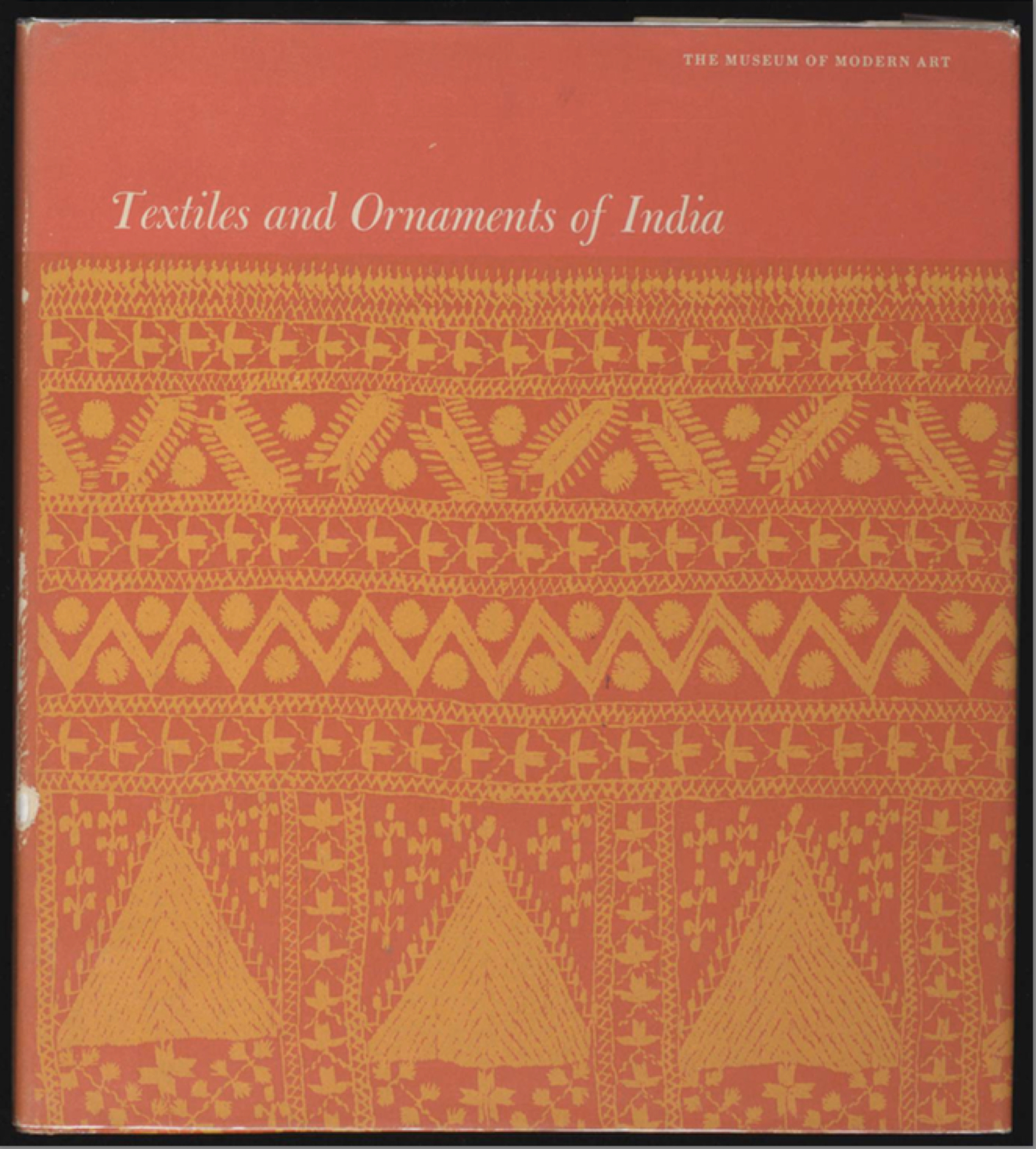

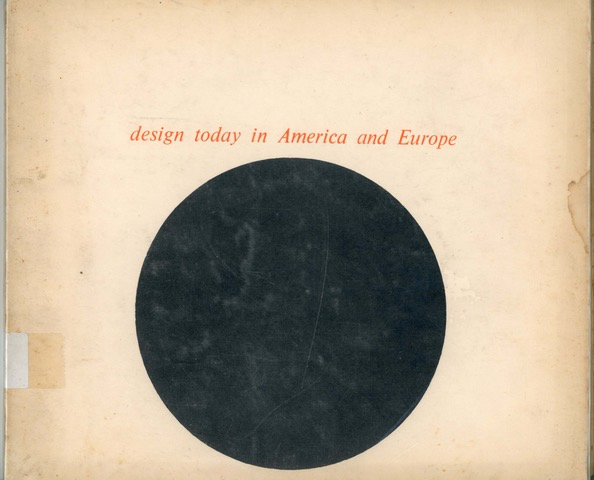

Charles Eames had been the designer of an exhibition titled Textiles and Ornamental Arts of India, held in 1955 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Jaykar had contributed an essay to its catalogue, and it was reported that the two met on the occasion of this exhibition. This led to an invitation from the Indian government to the Eameses. Presented as part of a series of cultural diplomacy initiatives between India and the United States, the MoMA exhibition had a counterpart in New Delhi, Design Today in America and Europe, which went on to travel to six other Indian cities.[2] With furniture and products for the home designed by some of the best-known international names at the time, the objects on display then became a permanent reference collection at NID, where it has remained since. It was intended to serve as the nucleus of NID’s educational pedagogy.[3]

-

Catalogue cover of the 1955 MoMA exhibition Textiles and Ornamental Arts of India. © Courtesy of Anjana Das-Hasper, Berlin -

Catalogue cover of exhibition Design Today in America and Europe by Arthur Drexler, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York Catalogue and exhibition installation designed by George Nelson and Company, New York. © Courtesy of Archives, National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad

Even the two exhibition titles say much about the respective approaches to hand production and industrial production at the time. At MoMA – which was presenting handmade contemporary objects of everyday use from India as “ornamental arts” – hand production was defined along the lines through which approaches to pre-industrial hand manufacture were considered. In post-war Europe, “Design” had emerged consciously as an entirely new entity, distinguishing itself from the “Decorative Arts” through its reliance on new and mechanized methods of production. Aesthetically as well, the two exhibitions were articulated as belonging to different realms: one to the cultural specificities of materials, processes of making, uses and symbolism and the other to the emerging, globally legible vocabulary of International Modernism, where regional markers often consciously disappear. Such Modernist sentiments were absorbed by NID as part of its mandate.

This binary between the decorative arts and international design informed how the craft-design relationship was subsequently established in post-independence India under the aegis of formal design education – and eventually in practice. In such developments, design began to be seen as a process of adding value to the manufacturing capabilities of craft.[4] In the decades that followed, the designer emerged in India as a new class of professional, as someone fundamentally distinct from a craftsperson or artisan. The designer was seen as a conceptualizer, involved with ideation, whereas the craftsperson aided in the production processes.[5] These roles were moreover distinct from the role of the artist. Such notions informed generations of creative practitioners in India and are in many ways still intact.

This approach – separating Art, Design and Craft – prevails even today. It is expressed in separate educational formats, academic theory, and the opportunities for showcasing practices as well as in different market networks and ecologies. Here, art is often seen as being concerned with philosophical ideas, serving people’s emotional needs. It raises and answers existential questions; one finds a way in art to speculate about a range of real and hypothetical matters, giving vent to the artist’s imagination. Art is an end in itself, whether in painting, sculpture or the constantly new forms it is allowed to take. Design, on the other hand, is seen as serving a whole different set of everyday, physical needs. As an industry or as an economic sector, it is obsessed with pre-empting or solving problems, evolving products and processes that cater to relatively utilitarian requirements. It occupies itself with questions of data, facts and surveys, dealing with user behaviour and patterns of consumption.[6]

For almost a half century from the time of NID’s inception as a design school, it offered training programmes under two broad disciplines: industrial design and communication design. The industrial design pedagogy was inspired by German teaching methods known from Ulm and the Bauhaus, both established in the early decades of the 1900s. The communication design curriculum drew on that of the Basel School of Design in Switzerland. NID’s textile department, under the umbrella of industrial design, was started by Helena Perheentupa, a Finnish designer who remained at its helm until the 1980s. The material and visual values of the early aesthetics that such curricula enabled – across disciplines – have influenced the trajectory of design in India to date. They have often been understood as having shaped an Indian Modernism, which drew on global ideas of the early- to mid-twentieth century, rooted in local inspirations, references and techniques of making.[7]

II

For a large part of the NID’s almost six-decade trajectory, “fashion” was considered a bad word. In the 1980s, the discipline of apparel design was introduced, with a strong emphasis on traditional Indian garment traditions and systems design. Alumni and graduates recall that even in the 1990s – after economic liberalization and economic reforms, when the Indian economy opened up to the world’s – NID’s discomfort with fashion remained palpable. Few, if any, were encouraged to participate in the new possibilities that the sector was developing. In parallel, the National Institute of Fashion Technology was established in 1987 (modelled on New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology) to train a new generation of designers, merchandisers and technicians to participate in the lucrative garment export sector, and it received substantial support from the government in terms of incentives.

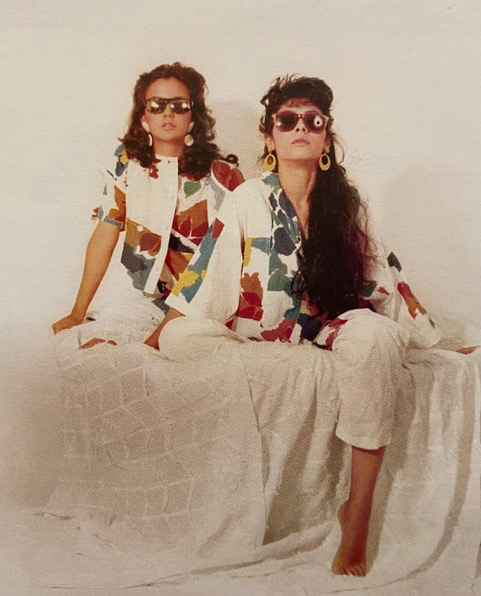

This period of 1980s ferment is often considered to have seeded the country’s organized fashion industry. In the ensuing climate, a new ecology of designers, stylists, fashion-show organizers and event managers, advertising professionals, models and photographers started articulating a new vision for Indian fashion. Some aspects of this looked to India’s historical past, focusing on the revival of textile traditions. Here Indian fashion was defined through references to and evocations of the country’s regional cultural diversity. Yet others looked to Western references, at a time when North America and Europe were seeing an unprecedented international expansion of their own fashion brands and industry. What remained common to both threads of Indian fashion, however, was an unflinching reliance on hand-craftsmanship.

With the arrival of cable television in the 1980s, moreover, Indian audiences were increasingly exposed to developments in film, fashion and culture in other parts of the world. Foreign brands optimistically explored entering the Indian market, and many found opportunities to advertise on a national scale that had not before been possible via popular channels like MTV and Channel V. Suddenly the Indian fashion designer emerged as a national celebrity, a role reserved until then primarily for actors, musicians and achievers in sports. Fashion designers started becoming household names in urban centres. But even as their stardom grew – their faces becoming increasingly familiar in the bourgeoning landscape of television channels, newspaper supplements and popular magazines – what they evoked in their work was the excellence, expressiveness and innovation of Indian craftspeople.

Today a multi-billion rupee industry, Indian fashion can attribute much of its rise to the Indian market category of occasional and formal-wear, which relies heavily on the use of hand-crafted processes such as Zardosi embroidery and hand block printing. It was during this time that Indian craftspeople attained the ambiguous status that they have largely maintained ever since: congratulated constantly for their talent in keeping alive the country’s rich cultural heritages, yet themselves anonymous and faceless. The anonymity in particular is a phenomenon that has only recently begun to be questioned. Needless to say, the circumstances leading to this cannot be traced alone to the parallel rise of the phenomenon of the Indian fashion designer. A range of other factors, both historical and contemporary, conscious as well as perhaps unintentional, have contributed to this. The above-noted acceptance of Westerncentric methods of categorizing (and separating) creative practices through the prism of Art, Design and Craft is one of these factors; Indian pedagogy borrowed from it considerably.[8]

Other factors include certain Indian social structures that continue to underlie the country’s major cultural, socio-economic and political fabric. Religious affiliation and caste have created historical inequalities that sometimes persist in textile arts, as in various other professions. In recent decades, many communities with longstanding associations with craft and artisanal activity have abandoned their hereditary occupations in favour of other employment opportunities. While this shift often offers a chance to improve their lives, it also involves relinquishing community identities. There is of course no place in a modern democracy for exploitative and discriminatory customs, whether social or financial – including, in extreme cases, caste-based bonded labour. Such conditions further express where craftspeople often find themselves vis-à-vis artists and designers: at the bottom of the pyramid of creative practitioners.

Another factor shaping attitudes towards crafts is the absence of the use of Indian languages for academic writing and curatorial work. But these are the languages of craftspeople themselves. Across the country, modern teaching in art, design and craft is taking place primarily in English. In the process, several specificities related to both terminology of creative production as well as to its role with reference to larger cultural conversations remain excluded from reflections on craft. The very absence of a word for “design” in Indian languages speaks volumes. And, as has often been pointed out, how are we to express trade terms and references that are used in such craft centres and which convey meanings and metaphors not easily captured in English?

III

In the resulting environment, the craftsperson remains largely represented by others and has comparatively little opportunity to make his or her own voice heard. Such arbitrations have shown the need for the crafts sector as an important economic sector and articulated – at different times – the requirements for appropriate governmental policy, even as non-governmental organizations and non-profits have emerged since the 1970s to address the ensuing gaps. In recent years, with the rise of interest in sustainable methods of production, the handmade is also being increasingly seen in this light as a valid future industry, beyond India, across the globe. Even then, the idea of craft and of the craftsperson in India tends for the most part to evoke an image of struggle – a sector in urgent need of being elevated.

I am both a maker-practitioner and a person reflecting through writing and curatorial formats on my own work in fashion, textiles, design and art. As such, my practice has attempted to question prevailing hierarchies among these fields. The following projects reflect ways in which I have sought to address some of the concerns expressed above:

Take Design

Having trained formally in a design school while also cultivating a strong interest in the visual arts and collecting practices, I was struck by the lack of galleries, museums and spaces for showcasing design in India, while these exist for the visual arts. The gap was additionally made wider by the absence of dedicated publications and reflective writing on the subject. This led in 2012 to a collaboration with Take on Art, a New Delhi-based magazine focusing on contemporary South Asian visual arts. The result was a special issue on design, which I guest edited. Aimed primarily at a visual arts audience, the idea here was to acknowledge the problems of defining design in the Indian context. By letting go of existing notions that design is necessarily a product of the Modernist, post-independence Indian milieu, the issue included essays that trace links of such modern and contemporary developments back to the so-called decorative arts from the late-nineteenth century. In doing so, the issue suggest a broader arc for understanding Indian design.

Fracture: Indian Textiles, New Conversations

For a 2015 exhibition that I co-curated with Rahul Jain and Sanjay Garg at the Devi Art Foundation, Gurgaon, a range of textile and non-textile practitioners were commissioned over a three-year period to collaborate with craftspeople. Here the idea was to acknowledge the role that the interdisciplinary approach plays in the emergence of innovative ideas of materiality and making. The presentation of the resulting projects gave equal acknowledgement to both types of practitioners. This was quite radical at a time when such commissions typically only showcased the designer’s name and left out the name of the craftspeople.

New Traditions: Inspirations & Influences in Indian Textiles, 1947–2017

A 2018 exhibition commissioned and presented by the Jawahar Kala Kendra in Jaipur was a survey of some of the key aesthetics that have shaped handmade Indian textiles in the years since independence. The featured textiles were made by a range of practitioners who identify themselves as artists, designers and craftspeople, by small studios and large companies, addressing the fashion and home furnishings sectors as well as representing rural and urban contexts. The curatorial principles emphasized the need to look at creative practices in textiles as a whole rather than relegating them to the specialized silos of Art, Design and Craft. Furthering the efforts of the 2015 show Fracture, practitioners were acknowledged as equals rather than through the inherent hierarchies that are so often implied between the fields.

Meanings, Metaphor: Handspun & Handwoven in the 21st Century

A three-part exhibition – presented in Chirala in the state of Andhra Pradesh, in Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu and in Bangalore in Karnataka – brought attention to a collection of 108 handspun and handwoven cotton textiles from 13 states in India. In Chirala, the exhibition became the core of a conference on handlooms and was viewed by close to four thousand weavers, along with almost three hundred delegates from around the world. The exhibition had a pedagogical component in offering the textiles as a study resource to weavers, who form the largest segment of the population in the town, which relies on handlooms as a major source of livelihood. By shifting an exhibition’s audience from the urban to the rural, and particularly to the makers themselves, the design suggested that textiles are themselves an accepted form of art and not a mere product or production process.

Mayank Mansingh Kaul is a New Delhi based independent curator and writer with an interest in post independence histories of textiles, design and fashion in India.

[1] Charles and Ray Eames, “The India Report” (Ahmedabad: National Institute of Design, 1958).

[2] Tanishka Kachru, “Bauhaus in Ahmedabad: Prototypes for Modernity”, paper given at the international conference Collecting Bauhaus, Bauhaus Dessau, 2019.

[3] Avinash Rajagopal, “Through American Eyes: The History of Exchange with the United States Reveals a Fundamental Dilemma of Indian Design”, Take on Art: Design, ed. Mayank Mansingh Kaul, special design issue of Take on Art, no. 7, March 2012.

[4] Based on conversations with Dr Suchitra Balasubrahmanyam as part of group sessions in Towards Global Histories of Design: Post Colonial Perspectives, a 2013 conference co-organized by Design History Society and NID.

[5] Several presentations at the 2020 NID conference Atoot Dor, organized to mark the fiftieth anniversary of NID’s textile department, discussed how the need to differentiate design from craft, fine and commercial art were important considerations among the educators at NID.

[6] National Design Policy, Government of India, 2007.

[7] Mayank Mansingh Kaul, “Prophets of Loom”, IQ: The Indian Quarterly, 2014.

[8] “Interview with Ritu Kumar”, in Cloth and India: 1947 to 2015, ed. Mayank Mansingh Kaul, special issue of Marg, June 2016.